In the Project for ArtBo 2022, Galeria Lume will present the works of Ana Vitoria Mussi and Gabriella Garcia. Ana Vitória's work sits in a conjunction of apparent paradoxes. It is focused on providing the status of experience to opacity, as a critical moment of looking. Her project can be viewed as the construction of opacity, as if specific clarity could resplend from there. Opacity gains the strange transparency of concept. Now the darkness, irreducible to the mere physicality of absence of light asserts itself as knowledge and circumstance. A veil veils a version of verity. It is the intermediation of the gaze. One doesn't read or see the fact anymore, but witnesses its invisibility. In a different way, by using the premise that objectivity is always a minimum of subjectivity, Gabriella Garcia invites us to shift our attention to the decay of any human classification system, building non-binary taxonomies that influence the body of works to be observed. Thus, the harmonious pigments, drapes, and stacks hide a barricade: instead of ordering, they accentuate the chaotic and inextricable character of the yearning for what may come to be valued as organization and delight. Garcia aims to demonstrate how the negationist use of taxonomic models such as archetypes, catalogs, lists, and indexes, simultaneously with liquid properties such as astrology, dreams, and memory, can be performed rhythmically and yet ironically. Bringing all these nuances of farces, invisibility and regrets in her works, both artists tensions the narrative power that the images created in the world and clarifies how questioning becomes extremely urgent and necessary so that history does not repeat itself as an even greater tragedy.

Lume was founded in 2011 seeking to foster and encourage the development of contemporary creative processes alongside with their artists and guest curators.

Headed by Paulo Kassab Jr. and Victoria Zuffo, the gallery dedicates itself to breaking down boundaries between different artistic languages, operating through a bold and unique model that reinforces the role of the city of São Paulo as a cultural hub and creative effervescence center.

The gallery represents a select group of artists, both established and emergent, dedicated to the introduction of artistic thinking in all of its mediums, aiming national and international audiences, through a plural exhibition program associated with ideas that inspire and promote critical reflections about the contemporary world. Lume is also focused on the dialog between the production of its artists and museums, institutions and relevant art collections.

Its active and organic presence in the circuit collaborates with the diffusion of the gallery’s propositions among the most important current art fairs in the world, apart from its participation and attendance in evolving alternative art fairs. Lume receives lectures, performances, seminars and artistic presentations in various natures. As a space of reflection and debate, it is also committed with the production of catalogues and issuing research material as a record of the gallery’s activities.

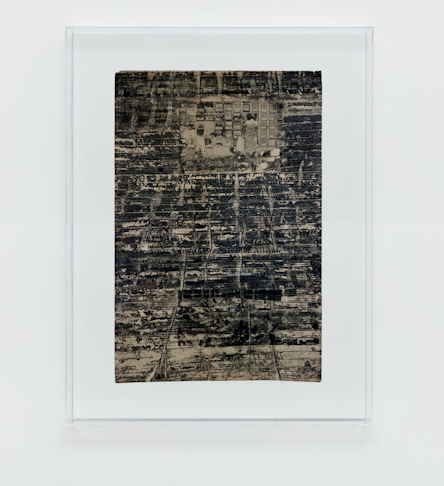

The Thin Thickness of the Image Some essential moments in Ana Vitoria Mussi’s work demonstrate that its evolution is connected to the ambiguous significance of the image, and not to the less complex field of formal and chromatic studies, inherited from abstractionism. Fewer than forty years ago, as much in Brazil as abroad, the hegemony of a pure art form, typical of Modern Art of the 1950s, began to lose ground in favor of a new interest in image, marked at this point by icons of mass communication and even the anonymity of daily life. Pop Art and its variations did not signify a simple return to classical mimesis or to figurative exercises of any kind, but to expressive waste, where a large portion of Abstract Formalism, both theoretical and practical, seemed to have arrived. In a field related to Modernist aesthetics, photography, cinema, and television appeared as imagistic alternatives to visual renovation, without returning to conventional images of classical iconography or owing to pictorial craft, whose depth extends from the pre-Moderns to the vastness of the past. Additionally, the intertwining of structural pieces with photosensitive images, being used since Impressionism — Dada, Surrealism — to the emergence of Pop, produced a sufficiently tested canon ready to be appropriated by Art, even if discretely, due to the predominance of an aesthetic centered on formal purity. In a partially Panofskian sense, it might be possible to distinguish, in the contemporary art panorama, the work centered on the aesthetic power of material elements (sensory form, color, gesture, material, texture, etc.) from those concerned with the semantic reverberation of the image beyond the field of strict formal self-reference, as intended by some modern isms such as Concretism. Mussi’s work is witness, with unequivocal quality, to a period in Brazilian art that goes from the birth of this new image, in the New Figuration of the 60s, to its unfolding in contemporaneity. From the beginning, when she produced work based on photographic interventions in newspapers (her series, Barreiras, 1972); passing through the documentation of boxing scenes (her series, Na TV, 1975-1996); through her inclusion of serigraphy, of experiences about limits (such as the exploration of matrices in her series, Res duos, 1993-1997); arriving at her current return to photography, Mussi has, from a strict point of view, explored various possibilities of registering and recreating light and shadow, producing them through the accumulation or rarefication of transparent and opaque materials. The technical image is radically different from the pictorial chromatics of Modernism, not only for its intrinsic reproducibility (Walter Benjamin), but also thanks to its eminently luminous and corpulent nature. The world of images distinguishes itself from the universe of forms, since it has not found in the materiality of the gesture, color, and the infinity of textures, the reason for its existence as a work of art — as form has. Inversely, images, like ghosts, extract quasi-immaterial elements (light and shadow) that constitute the force of a visibility inscribed upon minimal base structures. They content themselves with a merely visual, non-structural, configuration: ideas that are projected from the matrix (the negative) to the papers, canvases, screens (the work). There would be a sort of dislocated perception of an object since the work demands that the icon be separated from the matrix, and projected, as it were, from the negative of origin. All of Mussi’s work can be considered in the realm of this thin projection of image. If in the pages of her worked newspaper pages from the 60s, the series “Barreiras” and “Na TV” (photographed from newspapers with previous interventions and from television programs), the materialization of the image occurred through traditional enlargements. But in the work of the 1990s, the era of returning to art production after a decade long interruption, the situation became more radical. Her apprenticeship with screen-printing at Parque Lage, in 1989, brought new experimentation to Mussi’s work that took her beyond the technical and institutional limits of the analog reproduction of photography, although still propelled by the hand-made characteristics of gravure. Subjected by the artist to a radical inversion of terms, the screen-printing process became also a means for registering on the printing screens the scars of photographic transmigration. This double-handed operation, to transform the points of production of screen-printing into works of art, ends with the separation of matrix and printing, reintegrating them as equivalent material residues of a single process. The light itself, captured by the transparency, doesn’t record the world anymore, just holds it for a little while.

The Thin Thickness of the Image Some essential moments in Ana Vitoria Mussi’s work demonstrate that its evolution is connected to the ambiguous significance of the image, and not to the less complex field of formal and chromatic studies, inherited from abstractionism. Fewer than forty years ago, as much in Brazil as abroad, the hegemony of a pure art form, typical of Modern Art of the 1950s, began to lose ground in favor of a new interest in image, marked at this point by icons of mass communication and even the anonymity of daily life. Pop Art and its variations did not signify a simple return to classical mimesis or to figurative exercises of any kind, but to expressive waste, where a large portion of Abstract Formalism, both theoretical and practical, seemed to have arrived. In a field related to Modernist aesthetics, photography, cinema, and television appeared as imagistic alternatives to visual renovation, without returning to conventional images of classical iconography or owing to pictorial craft, whose depth extends from the pre-Moderns to the vastness of the past. Additionally, the intertwining of structural pieces with photosensitive images, being used since Impressionism — Dada, Surrealism — to the emergence of Pop, produced a sufficiently tested canon ready to be appropriated by Art, even if discretely, due to the predominance of an aesthetic centered on formal purity. In a partially Panofskian sense, it might be possible to distinguish, in the contemporary art panorama, the work centered on the aesthetic power of material elements (sensory form, color, gesture, material, texture, etc.) from those concerned with the semantic reverberation of the image beyond the field of strict formal self-reference, as intended by some modern isms such as Concretism. Mussi’s work is witness, with unequivocal quality, to a period in Brazilian art that goes from the birth of this new image, in the New Figuration of the 60s, to its unfolding in contemporaneity. From the beginning, when she produced work based on photographic interventions in newspapers (her series, Barreiras, 1972); passing through the documentation of boxing scenes (her series, Na TV, 1975-1996); through her inclusion of serigraphy, of experiences about limits (such as the exploration of matrices in her series, Res duos, 1993-1997); arriving at her current return to photography, Mussi has, from a strict point of view, explored various possibilities of registering and recreating light and shadow, producing them through the accumulation or rarefication of transparent and opaque materials. The technical image is radically different from the pictorial chromatics of Modernism, not only for its intrinsic reproducibility (Walter Benjamin), but also thanks to its eminently luminous and corpulent nature. The world of images distinguishes itself from the universe of forms, since it has not found in the materiality of the gesture, color, and the infinity of textures, the reason for its existence as a work of art — as form has. Inversely, images, like ghosts, extract quasi-immaterial elements (light and shadow) that constitute the force of a visibility inscribed upon minimal base structures. They content themselves with a merely visual, non-structural, configuration: ideas that are projected from the matrix (the negative) to the papers, canvases, screens (the work). There would be a sort of dislocated perception of an object since the work demands that the icon be separated from the matrix, and projected, as it were, from the negative of origin. All of Mussi’s work can be considered in the realm of this thin projection of image. If in the pages of her worked newspaper pages from the 60s, the series “Barreiras” and “Na TV” (photographed from newspapers with previous interventions and from television programs), the materialization of the image occurred through traditional enlargements. But in the work of the 1990s, the era of returning to art production after a decade long interruption, the situation became more radical. Her apprenticeship with screen-printing at Parque Lage, in 1989, brought new experimentation to Mussi’s work that took her beyond the technical and institutional limits of the analog reproduction of photography, although still propelled by the hand-made characteristics of gravure. Subjected by the artist to a radical inversion of terms, the screen-printing process became also a means for registering on the printing screens the scars of photographic transmigration. This double-handed operation, to transform the points of production of screen-printing into works of art, ends with the separation of matrix and printing, reintegrating them as equivalent material residues of a single process. The light itself, captured by the transparency, doesn’t record the world anymore, just holds it for a little while.

The Thin Thickness of the Image Some essential moments in Ana Vitoria Mussi’s work demonstrate that its evolution is connected to the ambiguous significance of the image, and not to the less complex field of formal and chromatic studies, inherited from abstractionism. Fewer than forty years ago, as much in Brazil as abroad, the hegemony of a pure art form, typical of Modern Art of the 1950s, began to lose ground in favor of a new interest in image, marked at this point by icons of mass communication and even the anonymity of daily life. Pop Art and its variations did not signify a simple return to classical mimesis or to figurative exercises of any kind, but to expressive waste, where a large portion of Abstract Formalism, both theoretical and practical, seemed to have arrived. In a field related to Modernist aesthetics, photography, cinema, and television appeared as imagistic alternatives to visual renovation, without returning to conventional images of classical iconography or owing to pictorial craft, whose depth extends from the pre-Moderns to the vastness of the past. Additionally, the intertwining of structural pieces with photosensitive images, being used since Impressionism — Dada, Surrealism — to the emergence of Pop, produced a sufficiently tested canon ready to be appropriated by Art, even if discretely, due to the predominance of an aesthetic centered on formal purity. In a partially Panofskian sense, it might be possible to distinguish, in the contemporary art panorama, the work centered on the aesthetic power of material elements (sensory form, color, gesture, material, texture, etc.) from those concerned with the semantic reverberation of the image beyond the field of strict formal self-reference, as intended by some modern isms such as Concretism. Mussi’s work is witness, with unequivocal quality, to a period in Brazilian art that goes from the birth of this new image, in the New Figuration of the 60s, to its unfolding in contemporaneity. From the beginning, when she produced work based on photographic interventions in newspapers (her series, Barreiras, 1972); passing through the documentation of boxing scenes (her series, Na TV, 1975-1996); through her inclusion of serigraphy, of experiences about limits (such as the exploration of matrices in her series, Res duos, 1993-1997); arriving at her current return to photography, Mussi has, from a strict point of view, explored various possibilities of registering and recreating light and shadow, producing them through the accumulation or rarefication of transparent and opaque materials. The technical image is radically different from the pictorial chromatics of Modernism, not only for its intrinsic reproducibility (Walter Benjamin), but also thanks to its eminently luminous and corpulent nature. The world of images distinguishes itself from the universe of forms, since it has not found in the materiality of the gesture, color, and the infinity of textures, the reason for its existence as a work of art — as form has. Inversely, images, like ghosts, extract quasi-immaterial elements (light and shadow) that constitute the force of a visibility inscribed upon minimal base structures. They content themselves with a merely visual, non-structural, configuration: ideas that are projected from the matrix (the negative) to the papers, canvases, screens (the work). There would be a sort of dislocated perception of an object since the work demands that the icon be separated from the matrix, and projected, as it were, from the negative of origin. All of Mussi’s work can be considered in the realm of this thin projection of image. If in the pages of her worked newspaper pages from the 60s, the series “Barreiras” and “Na TV” (photographed from newspapers with previous interventions and from television programs), the materialization of the image occurred through traditional enlargements. But in the work of the 1990s, the era of returning to art production after a decade long interruption, the situation became more radical. Her apprenticeship with screen-printing at Parque Lage, in 1989, brought new experimentation to Mussi’s work that took her beyond the technical and institutional limits of the analog reproduction of photography, although still propelled by the hand-made characteristics of gravure. Subjected by the artist to a radical inversion of terms, the screen-printing process became also a means for registering on the printing screens the scars of photographic transmigration. This double-handed operation, to transform the points of production of screen-printing into works of art, ends with the separation of matrix and printing, reintegrating them as equivalent material residues of a single process. The light itself, captured by the transparency, doesn’t record the world anymore, just holds it for a little while.

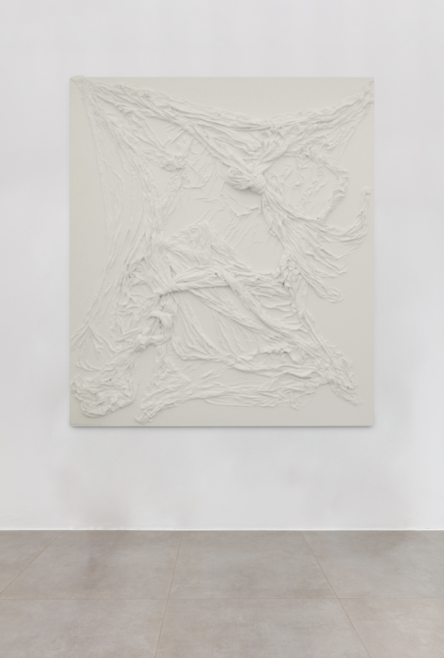

In Renaissance painting, it is known that what made a great work of art ideal was the absence of evident work traces, as if the image were simply an apparition that had not gone through the painter's hand, that is, based on the idea that neither a brush nor paint was used in its execution. In some paintings, however, the layers of paint became more transparent over time, allowing some images underlying the canvas to become visible. In this way, by revealing the alterations in the forms and compositions of these pictorial representations, the painter's changes of mind became visible, a phenomenon that in painting is called "pentimento." Pentimento (pentimenti) is an Italian word linked to the idea of regret. In her works, Gabriella Garcia elaborates a set of paintings and sculptures that deal, at first, with the idea of gestures and the very making of the art object. Nevertheless, the artist resorts to what is most academic and classic in art - whether in materiality or support - to justify an official history that has already been given. But those who think that Gabriella's aesthetic choices corroborate the reiteration of a hegemonic thought are mistaken. When we observe the theatricality employed in her works, we begin to realize that, there, every gesture may be staged and that the layers can hide nuances that the eyes cannot see. As in the Renaissance ideal, the artist creates objects that keep “regrets” within themselves. If we look at the history of dramaturgy, we notice that -like other realities in the universe of humanity- certain practices and certain characteristics apparently repeat themselves. If we pay more attention, though, we will find that they repeat themselves falsely, illustrating Karl Marx's claim that history happens twice: "the first as a tragedy, and the second as a farce." In Latin, the word "farce" implied the meaning of filling (farcire). The word has been used mainly in theater since Greece and gained special importance in the Middle Ages as a specific genre of spectacle. If the mimetic sense of the spectacle had to do with the imitation of a certain action, the farce presupposed a filling -that is, additions- and had to do with the masks that were originally made under this name. An original situation or character was "filled up," adding details and elements. To what end? With the purpose of criticism, such filling glass-magnified the quality or characteristic of the character or situation, intending to increase it, thus making it more visible and, consequently, more evident. By bringing all these nuances of farces and regrets in her work, the artist tensions the narrative power that the images created in the world and how questioning them becomes extremely urgent and necessary so that history does not repeat itself as an even greater tragedy. If, in the spectacle, farce served as a kind of criticism and mockery for those who watched, acting, thus, with a social function of morality; The works of Gabriella Garcia places us as spectators in a story full of flaws and, therefore, of layers that hide her real intentions. Now it is enough to know how to act in front of them. Recognizing that the world as we know it is nothing more than a mere constructed illusion can be painful, but doesn't this rupture also serve as a power to re-imagine the future?

In Renaissance painting, it is known that what made a great work of art ideal was the absence of evident work traces, as if the image were simply an apparition that had not gone through the painter's hand, that is, based on the idea that neither a brush nor paint was used in its execution. In some paintings, however, the layers of paint became more transparent over time, allowing some images underlying the canvas to become visible. In this way, by revealing the alterations in the forms and compositions of these pictorial representations, the painter's changes of mind became visible, a phenomenon that in painting is called "pentimento." Pentimento (pentimenti) is an Italian word linked to the idea of regret. In her works, Gabriella Garcia elaborates a set of paintings and sculptures that deal, at first, with the idea of gestures and the very making of the art object. Nevertheless, the artist resorts to what is most academic and classic in art - whether in materiality or support - to justify an official history that has already been given. But those who think that Gabriella's aesthetic choices corroborate the reiteration of a hegemonic thought are mistaken. When we observe the theatricality employed in her works, we begin to realize that, there, every gesture may be staged and that the layers can hide nuances that the eyes cannot see. As in the Renaissance ideal, the artist creates objects that keep “regrets” within themselves. If we look at the history of dramaturgy, we notice that -like other realities in the universe of humanity- certain practices and certain characteristics apparently repeat themselves. If we pay more attention, though, we will find that they repeat themselves falsely, illustrating Karl Marx's claim that history happens twice: "the first as a tragedy, and the second as a farce." In Latin, the word "farce" implied the meaning of filling (farcire). The word has been used mainly in theater since Greece and gained special importance in the Middle Ages as a specific genre of spectacle. If the mimetic sense of the spectacle had to do with the imitation of a certain action, the farce presupposed a filling -that is, additions- and had to do with the masks that were originally made under this name. An original situation or character was "filled up," adding details and elements. To what end? With the purpose of criticism, such filling glass-magnified the quality or characteristic of the character or situation, intending to increase it, thus making it more visible and, consequently, more evident. By bringing all these nuances of farces and regrets in her work, the artist tensions the narrative power that the images created in the world and how questioning them becomes extremely urgent and necessary so that history does not repeat itself as an even greater tragedy. If, in the spectacle, farce served as a kind of criticism and mockery for those who watched, acting, thus, with a social function of morality; The works of Gabriella Garcia places us as spectators in a story full of flaws and, therefore, of layers that hide her real intentions. Now it is enough to know how to act in front of them. Recognizing that the world as we know it is nothing more than a mere constructed illusion can be painful, but doesn't this rupture also serve as a power to re-imagine the future?

In Renaissance painting, it is known that what made a great work of art ideal was the absence of evident work traces, as if the image were simply an apparition that had not gone through the painter's hand, that is, based on the idea that neither a brush nor paint was used in its execution. In some paintings, however, the layers of paint became more transparent over time, allowing some images underlying the canvas to become visible. In this way, by revealing the alterations in the forms and compositions of these pictorial representations, the painter's changes of mind became visible, a phenomenon that in painting is called "pentimento." Pentimento (pentimenti) is an Italian word linked to the idea of regret. In her works, Gabriella Garcia elaborates a set of paintings and sculptures that deal, at first, with the idea of gestures and the very making of the art object. Nevertheless, the artist resorts to what is most academic and classic in art - whether in materiality or support - to justify an official history that has already been given. But those who think that Gabriella's aesthetic choices corroborate the reiteration of a hegemonic thought are mistaken. When we observe the theatricality employed in her works, we begin to realize that, there, every gesture may be staged and that the layers can hide nuances that the eyes cannot see. As in the Renaissance ideal, the artist creates objects that keep “regrets” within themselves. If we look at the history of dramaturgy, we notice that -like other realities in the universe of humanity- certain practices and certain characteristics apparently repeat themselves. If we pay more attention, though, we will find that they repeat themselves falsely, illustrating Karl Marx's claim that history happens twice: "the first as a tragedy, and the second as a farce." In Latin, the word "farce" implied the meaning of filling (farcire). The word has been used mainly in theater since Greece and gained special importance in the Middle Ages as a specific genre of spectacle. If the mimetic sense of the spectacle had to do with the imitation of a certain action, the farce presupposed a filling -that is, additions- and had to do with the masks that were originally made under this name. An original situation or character was "filled up," adding details and elements. To what end? With the purpose of criticism, such filling glass-magnified the quality or characteristic of the character or situation, intending to increase it, thus making it more visible and, consequently, more evident. By bringing all these nuances of farces and regrets in her work, the artist tensions the narrative power that the images created in the world and how questioning them becomes extremely urgent and necessary so that history does not repeat itself as an even greater tragedy. If, in the spectacle, farce served as a kind of criticism and mockery for those who watched, acting, thus, with a social function of morality; The works of Gabriella Garcia places us as spectators in a story full of flaws and, therefore, of layers that hide her real intentions. Now it is enough to know how to act in front of them. Recognizing that the world as we know it is nothing more than a mere constructed illusion can be painful, but doesn't this rupture also serve as a power to re-imagine the future?